Traumatic brain injury raises risk of brain atrophy

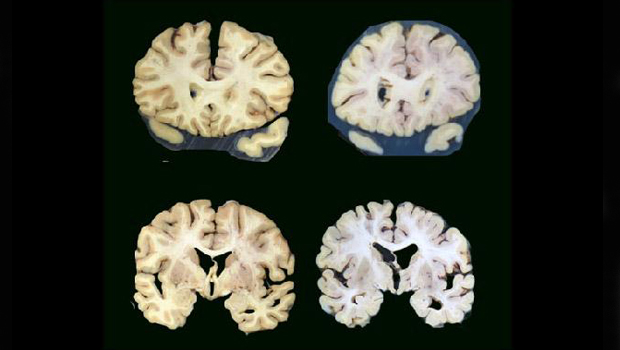

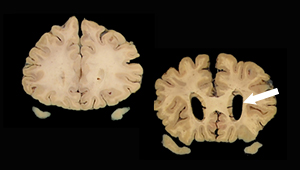

Brain on left is without significant atrophy. Larger spaces in brain on right indicate atrophy. (Photo credit: Lisa Keene)

Study suggests pathology of brain cell loss after traumatic head injury is distinct from Alzheimer’s disease

It has long been known that people who have had traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness have an increased risk of dementia. But it has been debated whether the increased risk was due to brain changes like those seen with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias or some other process.

Now a new autopsy study from researchers at the University of Washington (UW) School of Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI) has found that people who reported having lost consciousness after sustaining a traumatic brain injury faced a higher risk of brain atrophy, but not the changes associated with Alzheimer’s and related dementias. Brain atrophy is a loss of brain nerve cells and the connections between them. This often leads to decreased brain volume.

“Our finding adds to a growing body of research that suggests the pathological processes underlying post-traumatic neurodegeneration are distinct from those seen with Alzheimer’s disease,” said Laura Gibbons, a senior research scientist at the UW School of Medicine’s Department of Internal Medicine and lead author on the study. The article was published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

In the study, researchers compared the brains of people who reported having had head trauma with loss of consciousness with those of people who reported never having such an injury. The brains were donated by participants in the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) Study, a study of brain aging and dementia. Participants in the ACT Study were members of Kaiser Permanente Washington in the Seattle area who were randomly selected to be invited to participate. To qualify, they had to be 65 or older, living in the community, and not have dementia when they joined the study.

“This study is a great example of the type of research that a cohort like ACT makes possible, bringing together information from participants’ longitudinal visits, clinical records, and brain autopsies,” said Rod Walker, MS, a senior collaborative biostatistician with KPWHRI and co-author on the study. “We owe tremendous gratitude to the participants who have contributed to ACT’s success.”

At the time of enrollment and every 2 years thereafter, the participants underwent detailed health and cognitive assessments until they either died, developed dementia, or dropped out. As part of these assessments, researchers gathered information from the participants, their medical records and, in the event of their death or the onset of dementia, from interviews with family and friends about the participant’s history of head trauma, including whether it was accompanied by loss of consciousness, which can occur with more severe head trauma.

Examination of the participants' donated brains did not find more of the changes seen with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, such as amyloid plaques, in those who had brain injury with loss of consciousness. But they did find that those who had experienced head trauma with loss of consciousness were more likely to have brain atrophy.

The increase in risk for brain atrophy was small, “but it was statistically significant, so it’s likely real," noted C. Dirk Keene, the Nancy and Buster Alvord Endowed Chair in Neuropathology and professor of laboratory medicine and pathology at the UW School of Medicine, whose team examined the brains. The cause of brain atrophy in these individuals is unknown, Keene said. Keene is also an affiliate investigator with KPWHRI.

“We typically see atrophy as the downstream consequence of many other forms of neuropathology,” said Keene. “Strokes can cause atrophy, Alzheimer's-type neuropathological changes like amyloid plaques can cause atrophy, and so on. But we looked for everything else and did not find any other clear associations with [traumatic brain injury] — just atrophy itself. Atrophy is also a consequence of the diffuse injury to axons commonly seen after brain injury, so this finding supports axonal injury as a contributor to post-traumatic neurodegeneration. We still have a lot to figure out."

KPWHRI researchers and affiliates involved in the study were Rod Walker, MS; Kristen Dams-O’Connor, PhD; Dirk Keene, MD, PhD; and Paul Crane, MD, MPH.

The research was funded by the National Institute on Aging (U19AG066567, U01AG006781, P30 AG066509, pP50AG05136, AG0610280), the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U01NS086625-01), the Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (W81XWH-17-1-0330), and the Nancy and Buster Alvord Endowment.

This has been adapted from a news story written by Michael McCarthy for the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Learn About the ACT Study

Understanding brain aging

For over 30 years, the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) Study has been advancing our understanding of cognition, aging, and better ways to delay and prevent Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

News

New open data to help understand Alzheimer’s

Cell by cell, scientists are building a high-resolution map of brain changes in Alzheimer’s disease.

Research

Study evaluates biomarker criteria for Alzheimer’s risk

One-third of people classified as ‘highest risk’ may not develop Alzheimer’s disease, study suggests