Better tools for assessing substance use disorder

A study finds that a simple checklist developed at KPWHRI does well at measuring symptoms of substance use disorder

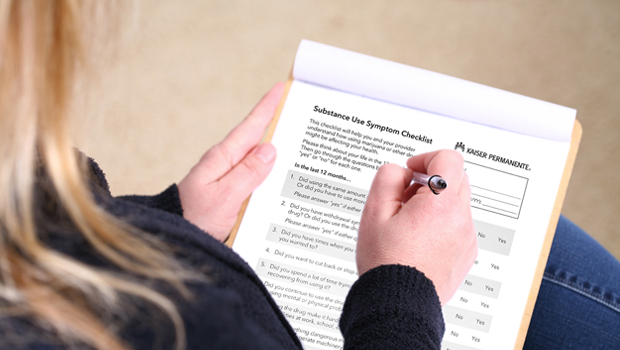

Since 2015 when Kaiser Permanente Washington began addressing behavioral health needs as part of primary care, patients have had the option to answer questions about issues they may have with cannabis and other substance use. Working with clinical partners, researchers at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI) developed an 11-item checklist based on the criteria for substance use disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Clinicians then began using the checklist as a tool in primary care to assess symptoms that people may be experiencing due to substance use.

Now a new study led by Tessa Matson, PhD, MPH, a collaborative scientist at KPWHRI, has confirmed the value of the checklist. Researchers used data from Kaiser Permanente Washington to evaluate the checklist’s performance, finding that it did well at providing information on the presence and severity of substance use disorder and did not show discrepancies in performance across age, race, sex, or ethnicity. The results were published in JAMA Network Open.

“The tool is helpful for clinicians to assess what symptoms patients are experiencing due to their substance use, and this study now tells us that the checklist is also a good overall measure of substance use disorder severity,” Matson said.

A simple, insightful checklist

This study is the first to evaluate performance of a substance use symptom checklist based on DSM-5 criteria in primary care. It is a companion to a recent study led by Kevin Hallgren, PhD, an affiliate investigator at KPWHRI, which evaluated the performance of an alcohol symptom checklist.

About 7% of adults in the United States meet criteria for substance use disorder, according to the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. But a much smaller percentage receive a diagnosis (between 0.8% and 4.6%, according to several studies).

“In primary care, it can be difficult for clinicians to talk to patients about substance use,” said Katharine Bradley, MD, a senior investigator at KPWHRI and the senior author on the study. “Time is limited, and prior to having this checklist, there was no easy way to assess substance use disorder symptoms in primary care. We developed the checklist to be a practical way to ask primary care patients about symptoms they may be having.”

This study included checklists completed during routine care by 16,140 patients who reported daily cannabis use only, 4,791 patients who reported other drug use, and 2,373 patients who reported both. In those groups, 26.3% of patients who used cannabis daily reported symptoms potentially reflecting a substance use disorder, as did 30.2% of patients using other drugs and 51.8% of patients using both cannabis and other drugs.

The checklist asks patients a series of yes or no questions, based on criteria from the DSM-5. The questions are designed to measure things like whether patients have increased tolerance to substances, whether they have withdrawal symptoms when not using a substance, and whether using a substance is affecting their daily life and mental health. Checklists are scored by adding the number of “yes” responses: 2 to 3 “yes” responses suggests mild substance use disorder, 4 to 5 suggests moderate, and 6 to 11 suggests severe.

“Measuring substance use disorder is challenging. We can’t detect substance use disorder on a physical exam, for example,” Matson said. “But we can detect its presence and severity by measuring symptoms. Our study looked at how well the checklist evaluated severity of symptoms, and whether it performed consistently.”

A successful measure

The researchers evaluated the checklist using a mathematical modeling approach called item response theory. This is a method designed to explain the relationship between a characteristic that is latent, meaning it can’t be observed, such as substance use disorder, and responses on a questionnaire, such as the checklist.

"By using item response theory, we test whether the questions in the substance use symptom checklist are measuring substance use disorder severity, and whether they're measuring it the same way for different patient populations,” Hallgren said.

The results showed that the checklist measured severity along a continuum, as intended. They also showed that each item on the checklist discriminated appropriately between higher or lower severity.

As part of the study, the researchers looked at whether the checklist performed differently depending on demographic characteristics like age, sex, race, and ethnicity. The results showed that small differences in item performance were not great enough to change the meaning or interpretation of checklist results. Overall, accounting for differences across subgroups resulted in less than half a point difference in total checklist score.

“Our results support continued use of this checklist as a tool to assess substance use disorder in primary care,” Matson said. “Clinicians have reported that it’s beneficial for finding out which symptoms patients may be experiencing, but now we have further evidence that it’s a psychometrically valid measure of substance use disorder severity. This information can then help clinicians make diagnosis and treatment decisions based on symptoms and severity.”

What’s next

Further research could build on these findings by interviewing patients to understand how they’d like cannabis use to be integrated into their medical care, Matson said. The checklist is currently used routinely at Kaiser Permanente Washington in primary care and as-needed in some mental health care visits. It would be valuable to understand how patients would like to have the results of the checklist communicated to them by providers and also what they understand about cannabis use disorder.

Researchers are conducting follow-up studies to understand the reliability of the substance use symptom checklist, its performance among patients with clinically recognized opioid use disorder, and differences in the performance of the checklist when completed online in advance of a primary care visit versus on paper during an in-person visit.

KPWHRI and KPWHRI affiliate coauthors on the study are Kevin Hallgren, PhD; Gwen Lapham, PhD, MPH, MSW; Malia Oliver, BA; and Emily Williams, PhD, MPH. This study was funded by grant UG1DA040314 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network.

By Amelia Apfel

Research

Better care for patients who drink alcohol

A new primary care approach improves alcohol-related preventive care as well as care for alcohol use disorder.

behavioral health

BHI: Easier access, better care, less stigma

Clinicians and staff at Tacoma South describe the many ways Behavioral Health Integration is making a difference for patients

innovating care

Asking patients about cannabis may benefit overall health

Drs. Lapham and Bradley find frequency of cannabis use can be tied to other behavioral health patterns and needs.

Research roundup

What's new in cannabis use research?

Use in pregnancy and screening in primary care studied by KPWHRI’s Kiel, Matson, and Lapham.