Greater infection risks linked to COVID-19 disparities

Multiple social factors may raise infection risks, including having a job that requires contact with the public, such as working in a grocery store.

New work by Susan Shortreed, PhD, finds infection risks drive worse outcomes for some racial and ethnic groups

Overall in the U.S., COVID-19 death rates are twice as high among people who self-identify as American Indian or Alaska Native, Black or African American, and Hispanic or Latina/Latino compared to white individuals. The reasons for these disparities are now clearer, thanks to new results from an analysis led by Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute Senior Investigator Susan Shortreed, PhD.

"We used data on more than 1 million people to determine if racial and ethnic disparities were due to a higher infection rate or due to disparities in disease progression," Shortreed said. "Our analysis indicated that higher risks of COVID-19 infection drive disparities in outcomes for Black/African American and Hispanic/Latina/Latino groups." In the study, the authors emphasized that social factors related to COVID-19 exposure, rather than biological differences, influenced higher rates of severe disease.

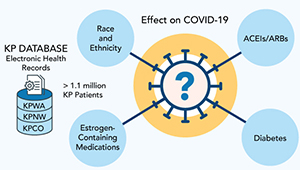

The researchers used data from the Kaiser Permanente regions in Washington, Colorado, and the Northwest (covering Oregon and Southwest Washington), looking at COVID-19 infections documented in the electronic health record from March through September 2020. The anonymized records were used to determine links between self-reported race and ethnicity and severe COVID-19 outcomes, defined as mechanical ventilation or death. The extensive data allowed Shortreed and team to conduct analyses that considered factors that might contribute to severe disease such as diabetes or obesity. They also studied only the group of patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis confirmed in the electronic health record by a PCR or similar test.

Disparities confirmed, infection identified as a factor

The study population was about 69% self-reported white, 9% Hispanic/Latina/Latino, 7% Asian American, and 4% Black/African American. The analysis confirmed that, overall, people in these 3 minority racial and ethnic groups were twice as likely, in general, to have severe COVID-19 outcomes even after taking into account other factors that might influence disease severity.

Further analysis of only patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis showed a lack of significant differences in severe outcomes after infection for the Black and Hispanic racial and ethnic groups. However, risks of severe COVID-19 after diagnosis remained more than 1.5-fold higher for the Asian American sample. Conclusions could not be drawn about the Indigenous American/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander samples because of the small number of individuals who self-identified in these groups, leading the authors to call for further study in samples with more diverse representation.

Since the individuals with Black and Hispanic self-reported race and ethnicity had worse COVID-19 outcomes overall but did not have higher risks of progression to severe disease once they had a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis, the researchers concluded that COVID-19 racial and ethnic disparities originate with greater risks of infection. The reason that people reporting Asian American race had higher risks of progression to severe COVID-19 is unknown. The results led the researchers to recommend further studies — for example, looking at specific Asian American subgroups — to find factors contributing to those disparities.

Potentially greater social risks

The authors point to multiple social factors that may raise infection risks for some racial and ethnic groups. These factors include having jobs considered essential that require working onsite and in person — for example, in food preparation, grocery stores, or health care. These jobs may not offer paid sick leave or time off for an employee who wants to get tested for COVID-19 and wait for results. The study was conducted when vaccines were not yet available. The study authors emphasized the importance of equity in distributing vaccines, now that they are widely available, to mitigate disparities.

The data used for this study were from before treatments such as the COVID-19 molnupiravir and ritonavir pills received Emergency Use Authorization from the U.S. FDA (Food and Drug Administration) to reduce risk of progression to severe disease. These measures offer hope of limiting severe disease, but the authors note that distribution of these and other treatments must be monitored carefully to prevent compounding racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 outcomes.

The paper: Shortreed SM, Gray R, Akosile MA, Walker RL, Fuller S, Temposky L, Fortmann SP, Albertson-Junkans L, Floyd JS, Bayliss EA, Harrington LB, Lee MH, Dublin S. Increased COVID-19 infection risk drives racial and ethnic disparities in severe COVID-19 outcomes. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022 Jan 24:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01205-2

Video

Race and ethnicity in analyses of health care data

Reflections from KPWHRI researchers Regan Gray, Rebecca Ziebell, Maricela Cruz, Yates Coley, and Jessica Chuback.

healthy findings blog

How is biostatistician Susan Shortreed improving care?

A love of problem-solving, math, and health science drive Dr. Shortreed’s work for better mental health treatment.

Drugs, diabetes, disparities

Studying COVID-19 risk and outcomes

Dr. Sascha Dublin tells how studies of KP electronic health record data can improve COVID-19 treatment and prevention.