Drugs, diabetes, and disparities: Studying COVID-19 risk and outcomes

Dr. Sascha Dublin tells how studies of KP electronic health record data can improve COVID-19 treatment and prevention

By Sascha Dublin, MD, PhD, senior investigator, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute; physician, Washington Permanente Medical Group, Internal Medicine

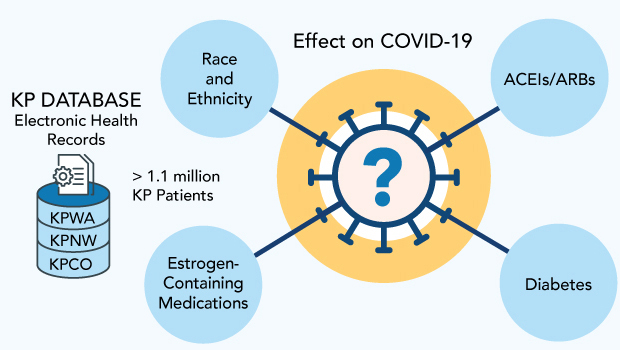

Currently, there is no definitive treatment for COVID-19. Researchers are examining a variety of risk factors that may impact disease susceptibility and severity, hoping to understand who is at highest risk and gain insights to tailor treatment. Many studies have used electronic health record (EHR) data: real-world data recorded during the course of clinical care that when used thoughtfully can shed light on the impact of chronic illnesses, prior medication use, and other patient characteristics on COVID-19 outcomes.

To address these questions, my colleagues and I are using EHR data from 3 Kaiser Permanente regions, serving about 2 million members, as the basis for 3 studies of COVID-19 infection and outcomes. As described below, one is examining the effects of medications that contain estrogen; another is focused on diabetes; and the third is looking at the impact of race and ethnicity. We received funding for this work from Kaiser Permanente’s Garfield Memorial Fund after proving its potential with a study last year of blood pressure medications.

Despite the growing availability of vaccines, the need for this type of research — focused on understanding risk factors for infection and severe disease — will persist in the coming years. Even in a best-case scenario, with 100% uptake of the vaccine among adults, a considerable population will remain at risk. Right now, children and teens are not eligible to receive the vaccine. Given the efficacy rates identified in clinical trials so far, if 5% to 34% of the adult population remains susceptible after vaccination, that would translate to between 16 million and 111 million adults in the United States alone. It’s likely to be more, given that many people are hesitant to be vaccinated, that immunity may wane over time, and that the virus is mutating, leading to new strains that may be less susceptible to current vaccines.

Fast track to guidance about medications and COVID-19 risk

Over the past decade I have led many studies that rely on large datasets using EHR data to analyze medication risks and benefits. In March 2020, as the pandemic took off in the United States, we saw a great need to launch a COVID-19 study that could be a proof-of-concept and lay the foundation for future EHR-based research on medications and risk of COVID-19 disease.

Roughly 1 of every 4 adults in the United States takes an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), most often to treat high blood pressure. As hundreds of thousands of people contracted the disease last spring, controversy emerged about these drugs and whether they might exacerbate COVID-19. This concern was based on these drugs’ potential effects on the ACE2 receptor, through which COVID-19 enters human cells. In contrast, other scientists hypothesized that they might reduce the potentially fatal lung inflammation characteristic of severe COVID-19 disease. These conflicting hypotheses left doctors and patients facing great uncertainty. While professional societies recommended patients continue on medications, they also called urgently for more evidence.

Before our team began its work, only a few papers had been published on the possible interplay between these drugs and COVID-19. Typically from China and Europe, the studies often involved relatively small numbers of patients, mostly those admitted to hospitals; few had a large enough sample to conduct rigorous, controlled analyses. By contrast, we had access to EHR data for more than 700,000 Kaiser Permanente Washington patients, of whom about 300,000 met all of our eligibility criteria. This allowed us to study not only the outcomes of patients with COVID-19 infection, but also to analyze who became infected in the first place, while controlling for many other characteristics. For instance, we could account for race/ethnicity and obesity, which most prior studies did not have the ability to study.

Our findings, first posted July 7, 2020 on the online pre-print server medRxiv and later published in the American Journal of Hypertension, clearly showed that these drugs neither increased nor decreased risk of COVID-19 infection. They also did not increase or decrease the risk of hospitalization among people who became infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing COVID-19. We were the first to examine daily doses of medications and could clearly show that people taking the highest doses were not at particularly high risk for bad outcomes. The research has contributed to a treatment consensus: People should not stop taking their ACE inhibitors and ARBs out of fear they will be at higher risk for COVID infection or more severe illness because of their medication use.

A sense of urgency had driven our work, and we produced the findings in roughly 3 months. Prior to the pandemic, this type of study often took 1 year or more.

Launching new studies

Our proof-of-concept study demonstrated how Kaiser Permanente researchers could offer insights that few others had the evidence to find.

A major strength is that we can study a well-defined population, and we can see almost everything that happens to them for which they seek medical care. Our EHR data go back years, with reports about when a person first was diagnosed with a particular condition, information on how long they have been taking certain drugs, lab results, hospitalizations, demographic detail that is not included in many types of records (such as insurance claims), and much more.

The records we have from Kaiser Permanente Washington include fairly large populations, and we have been able to enlarge the data set we used in the pilot study by partnering with colleagues from 2 other regions — Kaiser Permanente Colorado and Kaiser Permanente Northwest. We now have at our fingertips data for about 1.1 million people across the 3 regions who met our study inclusion criteria.

Kaiser Permanente’s Garfield Memorial Fund recognized the potential for the project and allocated funds to conduct the 3 new studies, now under way. We also have received support from the KPWHRI Small Grants Program (formerly the KPWHRI Innovation Fund).

Oral hormone therapy and birth control pills

Studies show that people with COVID-19 are at higher risk of blood clots. We also know that women taking estrogen-containing medications are at higher risk of blood clots. As a result of this commonality, a few medical societies have published guidelines advising women to stop hormone therapy and birth control pills if they develop COVID-19. While this makes intuitive sense, no actual studies have been published yet with data relevant to this decision. In addition, some scientists have hypothesized that estrogen may strengthen the immune system — which could be one reason that men have disproportionately died from COVID-19, more than women. Again, no epidemiologic studies have yet addressed this question. We intend to analyze EHR data to discern if these types of medications are associated with any change in incidence and severity of COVID-19.

KPWHRI Assistant Investigator Laura Harrington, PhD, MPH, is leading this study.

Diabetes

Data shows that people with diabetes are at high risk of experiencing more severe disease from COVID-19. We want to understand why. Our study asks a number of questions, including how people’s average blood sugar levels, as measured by hemoglobin A1C tests, correspond with the severity of COVID. We are not aware of any other study that has examined this relationship, which could have important clinical implications. For instance, if people with lower blood sugar levels — a sign that their diabetes is under control — have less severe COVID-19 outcomes, it could motivate doctors and some patients to work on managing blood sugars more aggressively.

Our study also will look at how the medication metformin is associated with COVID infection. This drug is mainly prescribed for people with diabetes, where it is a first-line treatment. If we find that its use corresponds with lower risk of infection, or of severe COVID-19 disease, this could suggest that it might be helpful for prevention or treatment of COVID-19. This could provide a motivation for future randomized clinical trials, for instance studying whether metformin use can prevent progression to severe illness in people with COVID-19. It might also motivate use of metformin as a preventive agent in people with diabetes who are not currently taking it, such as those with very mild diabetes not taking any diabetes medication. Metformin is a safe and inexpensive medication taken orally, which makes it particularly appealing.

These analyses are being led by James Floyd, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, and Jennifer Kuntz, PhD, an investigator at Kaiser Permanente Northwest.

Race and ethnicity

Deaths from COVID-19 have been disproportionately higher in the African-American, Pacific Islander, and Latino populations. There are many possible reasons for these discrepancies, including environmental factors (e.g., the likelihood of being an essential worker, or living in a multigenerational household) or medical factors (members of these communities are more likely to have diabetes or hypertension, known risk factors for severe COVID-19). Our study poses a series of questions including these 2:

- Whether the higher mortality rate may arise from a greater incidence of infection among African Americans, Latinos, and Pacific Islanders than among white people, and

- Whether people of color who do develop COVID-19 experience more severe illness than white people who become infected with COVID-19.

This information is vital to reduce racial and ethnic disparities. For instance, if we find that people of color have a higher infection rate, that could indicate that these communities are being more exposed to the virus. Perhaps their lives are more likely to put them in public spaces and homes where social distancing is less possible. In that case, the finding would indicate an urgent need for better support and more preventive measures for communities of color, such as better access to COVID-19 vaccines or personal protective equipment (PPE), for instance tight-fitting masks.

But if the infection rate among people of color isn’t higher, then it becomes even more important to analyze severe outcomes (such as mechanical ventilation or death) among people with COVID-19. Our study will tease out whether other factors, such as prevalence of diabetes and hypertension, have stronger associations with severe disease than race and ethnicity. Were that to be so, the response could be to increase efforts to manage diabetes and hypertension in these communities.

KPWHRI Senior Investigator Susan Shortreed, PhD, is leading this study, collaborating with Research Specialist Regan Gray, MS, and Biostatistician Mary Akosile, MS, MPH, both leaders of equity, inclusion, and diversity in science and research at KPWHRI.

What’s next

We recently finished pulling data at all 3 Kaiser Permanente regions in our dataset and are starting to analyze it. We will have the opportunity to study about 7,000 cases of COVID-19 infection, many in Kaiser Permanente members with de-identified records going back many years. Few researchers have access to such deep data.

Study findings may be ready to share as soon as April 2021. We are pushing hard to finish fast because we hope that our work could help save lives. We are trying to find answers that will be useful to guide COVID-19 care and reduce suffering due to the pandemic, not just for Kaiser Permanente members but for everyone. I believe that these first studies are just the start.

In addition to Dr. Dublin, the project involves the following project managers, programmers, and researchers: Elizabeth Bayliss, Lisa Pieper, and J. David Powers from KPCO; Stephen Fortmann, Jennifer Kuntz, Mi H. Lee, and Jan Van Marter from KPNW; Ladia Albertson-Junkans, Sharon Fuller, Laura Harrington, Susan Shortreed, Lisa Temposky, and Rod Walker from KPWHRI; and James Floyd from University of Washington.

Medication safety

Ensuring safe medications for older adults & pregnant women

In this short video, Dr. Sascha Dublin tells why KP is an ideal place to pursue her passion: Research to help vulnerable patients get the right drug treatment.

Research

COVID-19 pandemic research at KPWHRI

Having long tracked infectious diseases and tested vaccines, KPWHRI now focuses on the novel coronavirus.

News

NIH-Moderna COVID-19 vaccine receives FDA Emergency Use Authorization

The investigational vaccine that KPWHRI’s team first tested shows an efficacy rate of about 94% as research continues.