Cancer screening in the time of COVID-19

Dr. Diana Buist reflects on the challenges of providing screening during a pandemic — and finds reason for optimism

By Diana Buist, PhD, MPH, senior investigator and director of research and strategic partnerships at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI)

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged the health care system in extreme and unprecedented ways. And it will likely be years before we fully understand the extent of its impact, both on people’s health and how they receive care. My central focus — cancer screening — provides a useful example of the pandemic’s wide-ranging effects as well as a glimpse of its possible silver linings.

Cancer screenings on hold

With widespread stay-at-home orders put in place early in the pandemic, in-office visits to doctors’ offices and other health facilities were severely limited and people were advised to put routine cancer screenings on hold. The resulting drop in screenings was swift and steep: As of April 25, 2020, breast cancer and cervical cancer screening had each dropped 94% and colorectal cancer screening had fallen 86%.

Although cancer screening rates rebounded some when pandemic restrictions eased, in-office screening services have remained lower than before the pandemic, as providers have curtailed available appointments to prevent virus exposure and spread, and individuals have remained reluctant to come in for preventive care appointments.

While the full impact of these screening delays remains to be seen, analyses suggest U.S. health care organizations may be missing or delaying tens of thousands of cancer diagnoses. This could mean more cancers being diagnosed at a later stage, raised cancer incidence (for cervical and colorectal cancers in particular), and greater morbidity and mortality.

The challenge now is to reduce these harmful effects by making the best use of the limited screening capacity while also exploring ways to make screening more accessible.

Using data to guide screening strategies

Delays in cancer screenings nationwide have created a large backlog of people needing screening at a time when screening capacity remains limited. This provides the opportunity and incentive to develop more tailored screenings to prioritize services for those most likely to be diagnosed with cancer.

To help prioritize screenings for breast cancer, Diana Miglioretti, PhD, KPWHRI affiliate investigator and Dean’s Professor of Biostatistics in the University of California Davis Department of Public Health Sciences, recently led a data analysis to develop risk-based recommendations for scheduling mammograms when facilities have reduced capacity.

In a rapid analysis of data on mammograms from 2014 to 2019 from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, the team found that detection rates for breast cancer varied widely based on breast symptoms, personal history of breast cancer, age, and clinical indications for mammograms. From this data, they identified combinations of individual characteristics and clinical indications associated with high, moderate, and low cancer detection rates. The research was funded through a rapid COVID-19 supplement by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and a paper detailing its findings is currently in review.

This type of analysis shifts the basis for prioritizing screenings from expert opinion to data-driven evidence, creating, arguably, a more equitable approach that makes better use of limited services during challenging times, such as the current pandemic. Similar analyses would likely be useful for other types of medical services as well, including screenings for other cancers.

There’s no place like home

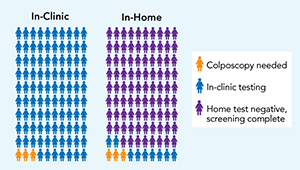

With limited availability of in-office cancer screening, home-based screening tests are getting renewed interest, as they allow people to be screened from the comfort, convenience, and — in the time of COVID-19 — relative safety of home.

Probably the best-known home screening tests are for colorectal cancer, including the fecal immunochemical test (FIT). These tests involve collecting a stool sample at home and then sending it to a lab for testing. This can identify individuals who may need an additional diagnostic test (colonoscopy).

A recent analysis published in Cancer suggests that screening rates for these tests have declined less steeply during the pandemic than rates for in-office screening tests such as mammograms and colonoscopies. The authors of the paper conclude that one positive outcome from COVID-19 could be a growth in home screening for colorectal cancer — and also for cervical cancer.

At-home screening for cervical cancer is common in some countries, such as Australia, Denmark, The Netherlands, and Malaysia. These self-collection tests look for high-risk strains of human papillomavirus (HPV) in a swab of vaginal cells collected at home. (HPV causes most cervical cancers.) They use a U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved assay to evaluate the presence of HPV; however, the FDA has not yet approved any self-collection swabs. Research suggests these home sampling kits are as effective at identifying high-risk HPV as samples collected during a traditional in-office Pap smear. And, as research at Kaiser Permanente Washington shows, they have the added advantage of convenience, which can boost screening rates.

I was the lead investigator for the HOME (Home-based Options to Make cervical cancer screening Easy) trial, which was the first randomized trial to study mailed HPV test kits in a U.S. health system. The trial — which included nearly 20,000 women who were overdue for cervical cancer screening — found that those who received the kit were 50% more likely to be screened compared with those who received usual care alone (annual patient reminders and outreach from primary care clinics). In a survey of participants of the HOME trial, those who returned the kits were highly positive about the experience, suggesting that mailing HPV kits helped address barriers to in-clinic Pap screening — a finding that takes on new significance in the context of COVID-19.

We are excited to have just started a follow-on trial including 33,000 women — called the STEP (Self-Testing options in the Era of Primary HPV screening for cervical cancer) trial — which will be ongoing for the next 2 years.

Looking forward to a post-pandemic future

Home-based tests and data-prioritized screenings were among the topics discussed at a virtual meeting I recently attended of the President's Cancer Panel, an advisory group that reviews the National Cancer Program. The meeting — titled Improving Resilience and Equity in Cancer Screening: Lessons from COVID-19 and Beyond — also covered several other strategies to improve cancer screening, including ways to expand outreach (particularly to people without access to good health care) and coordinate follow-up care after a positive screening result.

Although the discussions were wide-ranging, they shared at their center key questions about access and equity: How can we use available resources for the most benefit? How do we identify and reach out to people who need screening most? And how do we provide screening options that are convenient, accessible, and equitable? These are not, of course, new questions, but they have renewed urgency in the time of COVID-19. We’ll continue to look for answers that can help carry us through the pandemic and, ultimately, improve the future of cancer screening for all.

cancer screening

Mailing home HPV test may offer alternative to Pap screen

Dr. Diana Buist and team reflect on HOME trial showing 50 percent screening boost in underscreened women.

preventive care

Exploring at-home cervical cancer screening

Kaiser Permanente is at the forefront of research looking at using home tests for HPV, a leading cause of cervical cancer.

innovating care

How to maximize screening for colon cancer

Research informs care as Kaiser Permanente Washington, exceeding 80 percent screening rate, launches home-based 'FIT First' pilot.