What motivates Dr. David Arterburn to study obesity?

Dr. Arterburn with his sons, Charlie and Sam, in the Goat Rocks Wilderness.

He aims to reduce suffering from chronic illness. Plus, he's optimistic about research on body-weight regulation and on the psychology of weight-related behaviors.

David Arterburn, MD, MPH, is a senior investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI), an internal medicine physician at Washington Permanente Medical Group—and an affiliate professor of medicine at the University of Washington (UW).

What motivates you to do your work?

I am motivated by the suffering that is caused by chronic health problems. When I reflect on the most challenging times in my own life, those were times when I—or someone I loved—was dealing with a mental or physical illness. So, I want to be able to give people the same things that I wanted at those times: high-quality information, clear guidance, and access to treatment that can help put them on a trajectory towards wellness.

Most of my research is focused on obesity, which is arguably the biggest health problem we have globally, and especially in the United States. It’s so common and has such a pervasive impact on health, affecting every organ system in the body. Obesity-related chronic conditions cause a lot of suffering. And people living with obesity suffer emotionally from social stigma at work and in relationships with other people.

I hope that my work on obesity can help people to reduce their weight and their suffering—and help them better understand obesity’s causes and their treatment options. My work is incredibly satisfying because everybody can relate to the challenges of eating healthy and staying active in our modern lives. And most people have loved ones who’ve struggled with their weight, even if they themselves haven’t.

Even though the prevalence of obesity has been steadily growing in the past several decades, I’m optimistic about obesity research and the future of obesity treatment. We’re making big advances in understanding how body weight is regulated and how human psychology drives our behaviors. Mindfulness, motivational interviewing, and mobile device technology are showing great promise here. I believe that in my lifetime we’re going to figure out how provide effective, scalable, and affordable lifestyle interventions for obesity. And medications and surgery will have an even greater role to play for select patients with obesity who stand to benefit the most from those treatments.

How did you start studying obesity?

When I did my internal medicine residency in San Antonio, it had the third-highest rates of obesity in the country. I cared for patients in a community health clinic who were suffering from all sorts of weight-related health conditions like diabetes and cancer. We treated those conditions, but I was motivated by a clear sense that my patients—and my colleagues—were at a loss about how to effectively and safely address the underlying cause of these problems: obesity.

Of course, we suggested exercise and diet. But we just didn’t have the resources we needed to provide real support for behavior change. And San Antonio is so hot, it’s hard to exercise outside. And the typical American diet there is so unhealthy, loaded with fat, sugar, and processed foods. And unfortunately, there were few other options. As I showed in one of my first research studies, the weight loss drugs available at the time were either unsafe or ineffective, and very few people were even thinking about surgical obesity treatment at that time.

When I started my residency, my career was headed toward teaching clinical medicine, and I didn’t think I would do research. But some folks had a big impact on me. My program director, Mark Henderson, suggested I meet the general internal medicine faculty who did research. He introduced me to Cindy Mulrow, who became my first research mentor. With Cindy’s guidance, I studied the benefits and risks of drug therapy for obesity. She helped steer my career trajectory away from just teaching and toward a career in health services research, where we study how to best organize, manage, finance, and deliver safe, high-quality care.

Dr. Arterburn with his wife, Kristen Holway, a Global Business Manager for Google, in the Goat Rocks Wilderness

What first got you interested in shared decision making?

Again, it was all about mentorship. As an assistant professor at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and Cincinnati Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, I signed up for the Society of General Internal Medicine’s (SGIM) mentorship program. I was lucky enough to be assigned to Michael Barry, who’s at Mass General and was soon to become president of the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation. We met once face-to-face at SGIM. Then the next time I heard from him, he was calling to ask, “Do you want to help us develop a decision aid for people with severe obesity who are considering bariatric surgery?” I jumped at the chance.

That one phone call really helped launch my research career. Since then, I’ve spent most of my time on bariatric surgery and shared decision making: the intersection between them, and each of them separately. Shared decision-making is important for people with severe obesity as they consider their options, including intensive lifestyle changes, drug treatment and various types of bariatric surgery. Bariatric surgery includes different operations to change the digestive system and help people with severe obesity to lose weight. And in shared decision making, health care providers make sure of two things: that they elicit and understand what their patient’s individual preferences are; and that their patients are well-informed about the benefits and risks of all the available options. People need to know all their options, not just the ones that their provider likes best.

Because mentorship has had such a huge impact on my career, I feel like I must pay it forward. I’m here in this position because of all those mentoring moments—sometimes very brief ones—that shaped who I am today. I owe it to the next generation of researchers to be available and help move their careers forward as my mentors did for me. Working with many mentees now, I can already see the impact that they’re having on the health of others. It’s a multiplier effect of alleviating suffering and improving health and quality of life.

Collaboration has also been key to my work. As a VA research fellow, I began a fantastic working relationship with Matt Maciejewski, who’s at Duke and the Durham VA Medical Center. We are still doing national studies together to understand more about the long-term health outcomes of veterans who get bariatric surgery. He’s my longest-term collaborator, and our work on understanding bariatric surgery’s risks and benefits has affected the health of many people through the VA and beyond.

What makes Kaiser Permanente a good place to do your work?

Several things make this a wonderful place for me. A big one is the caliber of the people on the teams in the Research Institute: biostatisticians, programmers, project managers, and research specialists. They put patients’ safety and confidentiality first. And they’re very supportive of each other as well. It’s the kind of work environment where we challenge each other to get better at what we do.

I’m also impressed with how clinical leaders at Kaiser Permanente in Washington (KPWA) are eager to innovate to improve patients’ quality of care. I get to work directly with clinical leaders on implementation and evaluation, including working on shared decision making with Matt Handley and his team in Quality and Safety. Working with clinical leaders and administrators, we’re evaluating innovations quickly and co-creating science that’s likely to have a real impact on care.

We partner on initiatives like the Learning Health System (LHS) Program. In one part of that program, we’re looking at the problem of unwarranted variation. That’s when some providers or clinics are providing way more—or less—of a test or treatment than others are, and that variation isn’t explained by the characteristics or preferences of informed patients. Shared decision making is one solution to unwarranted variation; when patients are well-informed and providers help them to make decisions that are best-aligned with their preferences, the variations we see in clinical care are warranted. We’re trying to systematize the way we look for unwarranted variations in care, so we can target the tests and treatments that are most common, costly, and invasive—and that have the most variation. Then we want to do better shared decision making around them.

Since coming to KPWA, I’ve had many opportunities for collaboration. With colleagues at the UW and community partners, I’m studying which elements of the neighborhood built environment are linked to a healthy weight. Collaborating with far-flung Kaiser Permanente colleagues, particularly Karen Coleman in Southern California and Steve Sidney in Northern California, has been fantastic. Together we found that diabetes goes into remission for an average of seven years in people who have gastric bypass surgery. I’ve also gotten to partner with other Kaiser Permanente researchers and other integrated care systems in the Health Care Systems Research Network. We recently found that, compared to usual care, bariatric surgery is associated with fewer heart attacks and strokes—and less eye, kidney, and nerve disease—in people with diabetes and severe obesity.

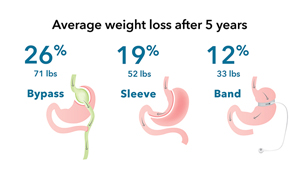

Kaiser Permanente has also been a leader in the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet®), which is taking research collaboration to a whole new level, rapidly conducting national studies with enormous data capacity and impact. One highlight of our PCORnet® research for me is working with patient partners who’ve informed which questions we asked and how we did the science. Their involvement makes our research that much more likely to have a clinical impact, because it was driven and motivated by what patients really wanted to know. Our PCORnet® Bariatric Study is groundbreaking in terms of the number of health systems participating—41!—and the length of follow-up as well. We recently reported that adult and teenage patients had the most long-term weight loss with gastric bypass surgery, followed by sleeve gastrectomy, and finally adjustable gastric banding. We’re now looking at how these bariatric procedures affect diabetes outcomes and long-term safety.

Dr. Arterburn on a summer ride around Vashon Island.

What keeps you going outside of work?

I love to spend time with my sons, who are both teenagers, navigating high school and making decisions about college. I try to encourage their development and model a healthy lifestyle for them. I’ve developed a good practice of meditating and exercising almost every day. On a typical day, my wife and I usually meditate for 15 minutes in the morning, but about once a week we sit for 40 minutes with the Seattle Insight Meditation Society. We also run, bike, hike, ski, and do yoga regularly, often with our friends. Most of my time outside of work, and a lot of my social network, are oriented toward those activities that help me maintain my mental and physical well-being.

Our own wellness often gets relegated to last place, but if we don’t make it a priority, it catches up with us. I know from experience that neglecting my wellness leads to poor health outcomes. How I spend my time outside of work relates back to the whole underlying motivation for my work in obesity. None of us is immune from suffering and struggles around our behavior. Maintaining our wellness requires sustained concerted effort to counterbalance the innumerable societal pressures we face to eat, drink, and work too much. We must create our own culture and structure our own environment in a way that supports our physical and mental well-being, so that we have the greatest chance to be happy, healthy, and live with ease.

Video

Which surgery is best for weight loss? Gastric bypass

Oct. 29, 2018—Dr. David Arterburn discusses results from the largest, long-term study of its kind, conducted by PCORnet® scientists and published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

(Vimeo 1:56)

News Release

Gastric bypass surgery is best for weight loss for severe obesity

Oct. 29, 2018—Largest long-term national study of bariatric surgery, comparing 3 most common operations, is among first PCORnet® results.

News Release

Fewer heart attacks, strokes, and deaths after weight-loss surgery

Oct. 16, 2018—Obese people with diabetes had fewer deaths in 5 years after bariatric surgery vs. usual care, in large, long-term study.

Video

Moving to Health

Where you live can affect your health, and a $2.67-million NIDDK-funded UW/KPWHRI project explores how.