Talking to an addictions researcher

KPWHRI Collaborative Scientist Leah Hamilton, PhD, MPhil, answers questions about her recent and upcoming projects

Research on how to effectively treat and prevent opioid use disorder is a priority area of work at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI). Collaborative Scientist Leah K. Hamilton, PhD, MPhil, is an addiction health researcher whose work focuses on improving care access and substance use treatment and services, particularly for people who have been involved in the criminal justice system. She is the lead author on a study that recently published in the International Journal of Drug Policy. The paper analyzed opinions from experts on the provisions of different opioid-related laws, asking them to rate the helpfulness of each provision and its perceived impact on overdose deaths. Dr. Hamilton answered questions about the study and her other research work at KPWHRI.

Why did you want to do this study? What motivates you to do research in this area?

I grew up in Vancouver, B.C., where substance use issues have long been a major concern in the city. Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside has one of the longest-running safe injection sites in North America. I was interested in working with people who have substance use issues in the criminal justice system, because they are a vulnerable population who often are treated inappropriately through a moralistic perspective rather than focusing on their health needs. Working with people with substance use issues who are touched by the criminal-legal system can require using a lot of different resources to figure out what is going to best help people be as well as possible. This is challenging, particularly as their involvement in the justice system carries substantial stigma.

During my postdoctoral research at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, I was able to work with a number of scholars who have been doing really interesting policy work on the opioid epidemic. This included research on Good Samaritan laws — which provide limited legal protections to people who assist someone in an overdose situation and sometimes provide protections for the person overdosing — as well as other laws and policies that are oriented around harm reduction, reducing criminalization of behaviors associated with drug use, and improving treatment access. I was interested in how those laws interacted with other laws around the opioid epidemic, especially their impact on overdose deaths.

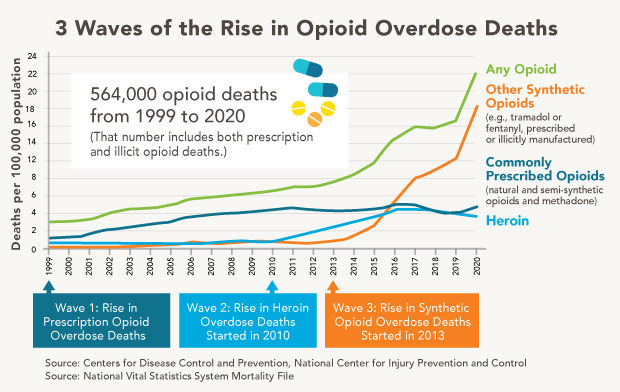

There have been multiple waves of the opioid epidemic, driven by different substances. The first wave was prescription opioids, then heroin, then fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. Policymakers have often been reactionary in the policy design when addressing each of these waves, and that often means that lots of policies get enacted at the same time. It’s difficult in that scenario to understand the interactions between these policies and what laws or specific law provisions matter in addressing the opioid epidemic. This study, with Principal Investigator Magdalena Cerdá, was an attempt to start trying to pull apart those threads.

Can you talk about how you did the work of analyzing these different policies?

We used a Delphi process, which is a method of collecting expert opinions to help identify consensus. We included experts across 6 different fields related to opioid policy: academic research, public health governance, clinicians, advocacy (including unions that represent people who use drugs), law enforcement and criminal justice, and industry. We started with focus groups, then did extensive recruitment across those stakeholder pools to whom we distributed 2 waves of surveys.

Then we took 8 different laws where we had systematic data available and broke them into their key legal provisions. The same law can be very different state to state depending on which provisions are included. For example, in naloxone access laws, does a state include provisions that guarantee immunity to the prescriber of naloxone (a medication to treat acute opioid overdoses), or to laypeople who distribute naloxone, or ro both (or neither)?

We had our experts go through each provision of each law and rate these different provisions on a scale from helpful to harmful and on a scale of impact. We’re trying to identify whether there are key provisions within laws that are perceived by experts to be particularly helpful or particularly harmful, and whether there is consistency in these opinions across different expertise types.

What did you find? Did anything surprise you?

There was a ton of agreement across expertise types. We often end up thinking that clinicians and public health officials don’t share the same opinions as people working in the criminal justice system, for example. But overall there was substantial agreement, particularly around what policies were helpful. The experts we talked to consistently rated laws facilitating harm reduction and access to treatment as the most helpful. There was a little more disagreement around harmfulness of certain laws, but only a couple of provisions with a substantial amount of disagreement. Drug-induced homicide laws (laws with provisions that add additional criminal penalties for people who sell or provide drugs to others), which further criminalize substance use behaviors, and laws requiring prior authorization for Medicaid coverage of medications for opioid use disorder were among the provisions that experts thought were most harmful.

What are the next steps?

The immediate next step research-wise is to create state profiles, describing the full policy environment for each state for each year where we have data by applying the score for each provision that they have. We then plan to validate whether these policymaker-generated scores add to the statistical modelling of the relationships between these laws and fatal overdoses.

The results from this paper are expert consensus, and they aren’t empirically validated yet. But there are a number of laws that we looked at that I think make substantial impacts on clinical outcomes, such as laws about naloxone distribution in a clinical setting that provide civil and criminal protection to clinicians who prescribe naloxone. In my work on partnering with clinical providers at Kaiser Permanente Washington and elsewhere, I know we work hard to assess folks for opioid use disorder and get them medication-based treatment, as we know it’s the most effective form of treatment out there. Greater policy support for providing medication for opioid use disorder and naloxone distribution would only improve our ability to care for patients who use opioids.

Hopefully this evidence, once it’s validated, can be useful for informing policy decisions, helping policymakers select the most effective legal provisions to address the opioid epidemic and reduce the use of ineffective and potentially harmful provisions.

What other research are you working on at KPWHRI?

My other avenue of research is around appropriate screening and access to care for people who use drugs and alcohol. The Kaiser Permanente integrated health system is an awesome place to be working on that. There’s been a lot of work on behavioral health by other researchers like Kathy Bradley, Amy Lee, and Gwen Lapham. We have a much better picture of what folks’ needs are in the system, and we can see how proper identification and linkage to care can lead to improvements in people’s health outcomes.

Since joining KPWHRI, I’ve gotten involved in several pragmatic clinical trials. One is the PROUD trial led by Kathy Bradley. Within that study is a nurse care management model for treating opioid use disorder in a primary care setting. I am looking at how participating in care for people with opioid use disorder can affect staff attitudes about opioid use disorder and its effectiveness and appropriateness as a part of primary care.

And I’m also involved in a newer project, the MI-CARE study, which is a collaborative care model for treating folks with opioid use disorder who have elevated scores on a standardized patient health questionnaire (the PHQ 9) indicating symptoms of depression. We are working with a model of measurement-based care to see if patients can decrease their depressive symptoms and increase their number of days of treatment for opioid use facilitated by a nurse care manage model.

I also have a grant in development to look at how many patients within the Kaiser Permanente population self-identify as having been involved in the criminal justice system, and whether that status has an impact on their health outcomes. We want to understand whether screening for this would help provide support for patients in the system who are dealing with legal needs.

The study “A modified Delphi process to identify experts’ perceptions of the most beneficial and harmful laws to reduce opioid-related harm” was published online July 28, 2022 in the International Journal of Drug Policy. Leah K. Hamilton, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute is the lead author. Magdalena Cerdá, DrPH, of the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, is the senior author. Co-authors are Katherine Wheeler-Martin, MPH, of the NYU Grossman School of Medicine; Corey S. Davis, JD, of the NYU Grossman School of Medicine and the Network for Public Health Law; Silvia S. Martins, MD, PhD, of the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health; and Hillary Samples, PhD, of the Rutgers Institute for Health and Rutgers School of Public Health. The study was funded by a National Institute on Drug Abuse award: #R01DA045872.

healthy findings blog

Partnering to advance lifesaving care

Amy Lee describes how the LHS Program is helping KP Washington track and improve treatment for opioid use disorder.

Research

HEAL responds to double crisis: Opioids and COVID-19

Health care is increasingly online—KPWHRI is studying telehealth options for opioid use disorder and chronic pain.

pain management

Six Building Blocks help small rural clinics to manage opioids better

Led by Dr. Michael Parchman, research team uses new way to support small clinics in reducing opioid use in rural Pacific Northwest.

healthy findings

Opioids: Encouraging trends and new challenges

Kaiser Permanente Washington led in reducing opioids. We’re now seeing benefits, but there’s more work ahead, writes Dr. Michael Von Korff.