Decades in the making: A look back at what makes MacColl, MacColl

MacColl Center co-founder Brian Austin, who is retiring this week, reflects on how the Center became a global pioneer in health care transformation

After a 37-year career at our research institute, including 28 years as the MacColl Center for Health Care Innovation’s founding associate director, Brian Austin is retiring this week. Established in 1992 with Dr. Ed Wagner at the helm, the MacColl Center was originally created to improve care in our delivery system (then Group Health Cooperative) by identifying, developing, and testing innovations in how care is provided to populations of patients. Since then, MacColl has developed a national and international reputation for leading effective health care transformation in primary care practices of all shapes and sizes, including those who serve our nation’s most disadvantaged populations. In this Q&A, we talk with Brian about MacColl’s many contributions over the years, his insights on what made their work successful, and the innovations he’s most proud of.

After 28 years of transforming health care, I’m sure you’ve had many ‘aha’ moments. Can you share one from MacColl’s early days?

I think my first was actually before MacColl was founded. Group Health approached our research institute in 1992 (we were the Center for Health Studies at the time) and said, in essence, “We have a world-class health services research firm within our walls. Why are we only reading journal articles like everybody else?”

At that point it became clear that we didn’t have to have as strong of a separation between the ivory tower and the trenches. Most of us have heard that traditional research takes 17 years to get implemented into practice. But Group Health didn’t want to wait 17 years, and it opened a new door. The MacColl Center was established with funds from the Group Health Foundation because Group Health was inviting researchers into the delivery system—not just as a laboratory, but to help make it better. And I’ve always been grateful for that.

MacColl’s early focus was specifically on developing, testing, and implementing improvements in care delivery at Group Health. And now, 28 years later, that vision has really come full circle with Kaiser Permanente Washington’s Learning Health System (LHS) Program. Co-led by MacColl Director Katie Coleman, MSPH, the LHS Program is proof that Kaiser Permanente Washington has a renewed commitment to improving care by leveraging our in-house scientific capabilities. I could not be happier that it’s happening now, and I think it’s the right work to be doing.

What stands out among the early work you did with Group Health?

Our high-water mark early on was participating in the Roadmap for Clinical Quality, which was a major organizational effort to improve care by incorporating current evidence and performing rapid-cycle testing to create new standards of care for chronic conditions like diabetes and heart disease.

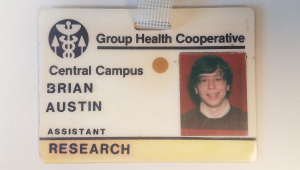

Brian’s first Group Health badge, photo taken in 1983.

Not only was this a true collaboration between our delivery system and our scientific staff, many of MacColl’s later advances grew from the roadmaps we created—such as our focus on population health, patient registries to drive proactive care, the reorganization of care staff, and the emphasis on patient self-management support. Ultimately, it was through the Roadmap effort that the tenets of the Chronic Care Model were developed.

The Chronic Care Model is certainly what MacColl is most known for. How did an internal improvement project at Group Health lead to a care model that’s been used and adapted worldwide?

The Roadmap project became a perfect laboratory for understanding the common issues across chronic disease areas. What did successful heart-failure interventions have in common with diabetes interventions have in common with COPD interventions? Credit goes to Ed and KPWHRI Senior Investigator (retired) Michael Von Korff , ScD, for looking at the scientific literature in a new way and thinking of chronic disease as a topic unto itself.

That led directly to white-board drawings in the mid-1990s showing the elements of successful interventions and how the delivery system could capitalize on that knowledge to redesign care to better meet the needs of people with chronic conditions. And that led to a one-year planning grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) in 1997 to refine this idea of a crosscutting “chronic care” model.

Next came more than a decade of funding from RWJF for Improving Chronic Illness Care, a nationwide “field building” effort to help spread the Chronic Care Model to as many delivery systems as possible by providing technical assistance and leading learning collaboratives. It was a happy accident that a representative from the Bureau for Primary Health Care attended our first collaborative. He came away feeling that every community health center in the country should be learning this stuff and launched a national program of Health Disparities Collaboratives that eventually involved more than 500 federally qualified community health centers nationwide.

Then our first international collaboration came in 2002 when we worked with the World Health Organization to re-imagine the Chronic Care model to be more internationally relevant—adding policy elements and strengthening the community components.

Did you ever imagine that those whiteboard drawings in the mid-90s would lead to that?

Only in that I knew Ed wanted to change the world. When I wrote MacColl’s original business plan in 1992, I envisioned that we had 3 years of funding and work ahead of us to help our delivery system. But I don’t think Ed would have ever been satisfied with working in just 1 delivery system. Being able to share what we learned with the broadest audience possible—I think that was always in Ed’s mind.

What’s made that a reality—and one of the things I’m proudest of—is that we’ve found ways to partner with organizations that could help us work with as many practices as we possibly could. We’ve had the opportunity to collaborate with vanguard organizations that are on the cutting edge of health care transformation—organizations like the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and funders not only like RWJF but also the Commonwealth Fund and the California Health Care Foundation.

And in our LEAP project, MacColl staff visited and learned from 31 high-performing primary care practices around the country, from rural clinics to federally qualified health centers to clinics within large integrated systems. Then we translated what we learned about what makes these practices exemplary into an online guide to implementing high-quality, team-based care.

What else are you most proud of in your long career at MacColl?

I’m proud that we’ve increased our focus on the safety net and on what I would consider more average practices—bringing our lessons learned to a more usual health care environment. To do that, we’ve had to expand our thinking around how improvement works in practices that may be less well-resourced, have higher staff turnover, and serve patients who need help the most.

With the Safety Net Medical Home Initiative from 2008 through 2013, we partnered with 65 community health centers in 5 states to implement the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model of care (see news release). And with Healthy Hearts Northwest, led by former MacColl director Michael Parchman, MD, MPH, from 2015 through 2018, we worked with more than 200 small and mid-sized practices in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. Our goal was to improve their ability to incorporate new evidence into practice and thus improve cardiovascular care (see news release).

Both these projects taught us a lot about the real-world challenges of working on quality improvement with well-intentioned but often overburdened practices.

How did learning about challenges in the safety net and in other real-world practices help shape MacColl’s more recent work?

One of the biggest challenges real-world clinics face is payment—they don’t get reimbursed for doing the care that chronically ill and other challenging populations need. Many of our recent projects have been more robust in thinking about the policy and business implications of health care improvement.

Katie has led most our work on integrating the business case for better care into improvement efforts. That work reached a new high point with the Delta Center for a Thriving Safety Net in 2018—a national collaborative driving toward policy and practice-level changes in value-based care and payment. Funded by RWJF, the Center provides technical assistance to state primary care associations and behavioral health state associations who support practices (see news release).

Another way we’ve tackled payment issues is with Michael Parchman’s Taking Action on Overuse project, where we’re looking at how to be good stewards of health care resources by decreasing unnecessary or harmful care (see news story). This is a natural step for MacColl: Stopping things that are ineffective is just as important to us as doing things that are effective—because it’s all the same money, and the same overworked staff.

What last piece of advice would you offer to your colleagues at MacColl who will continue to carry on the legacy of your and Ed’s vision?

My parting thought is that the magic of both the Center for Health Studies’ and MacColl’s early years was that, for each, it was like being at a startup. You felt like the future was open, that you had the resources to think big, and that you had the colleagues that would spark the best ideas.

So my advice would be to figure out how to keep the attitude of a brand new venture even as a larger, more mature organization—meaning that you’re nimble, you’re curious, you’re deeply engaged in your work, and you’re collaborating with people who might not fit in the normal mode of a scientific study. But they’re just who you need to think outside the box.

ACT Center

New center focuses on equitable, whole-person health care

Kaiser Permanente launches the Center for Accelerating Care Transformation.

social determinants of health

MacColl Center helps launch Delta Center for a Thriving Safety Net

New collaborative with John Snow Inc. and Center for Care Innovations aims to spur innovation in value-based payment and care.

news

What defines outstanding primary care leadership?

The MacColl Center’s LEAP project identifies 11 features of effective leadership at primary care practices.

recent news

6 Value Champions begin tackling medical overuse in the safety net

A new training and mentorship program supports clinicians in doing less of what harms and more of what helps vulnerable patients.